In the annals of aviation, few types of aircraft

have flown as both monoplane and biplane. The period between the

wars saw some experimentation with the monoplane configuration

using existing biplanes. A company developed an ejectable upper

wing for Hurricanes during the Second World War. The Pietenpol

folks developed a biplane version of the Air Camper called the

Aerial, STCs modded some high-wing utility aircraft with a lower

wing for crop-dusting.

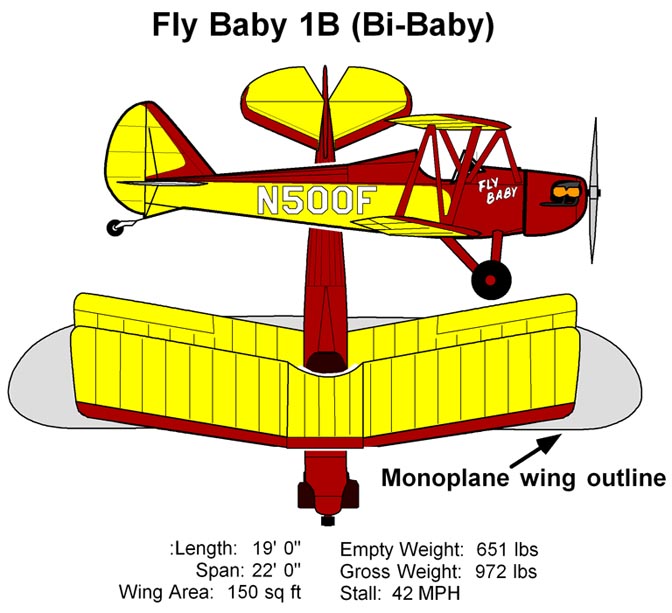

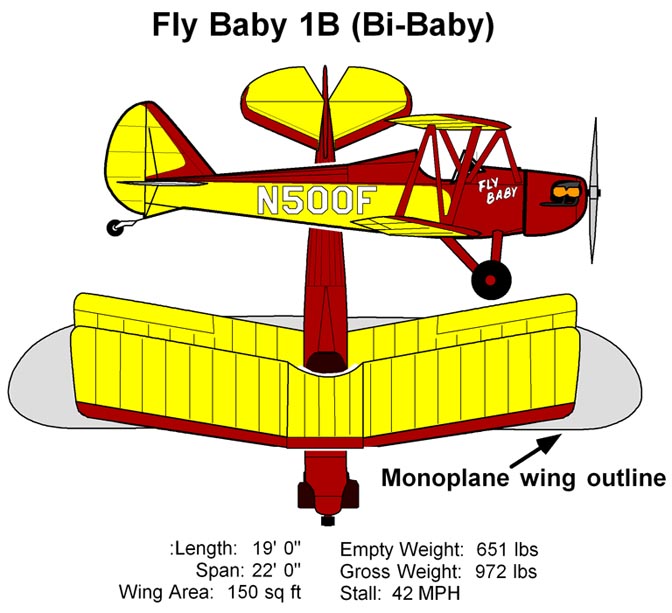

But of all the designs, only one let a pilot stand by the airplane and say, “Hmmm…shall I fly it as a monoplane or a biplane today?” And that’s Pete Bowers’ “Fly Baby.”

Pete pretty much planned flying a set of biplane wings all

along. In the December 1962 issue of EAA’s SPORT AVIATION

magazine, he wrote, “…when it was decided to use three different

wing arrangements for versatility, the designation was expanded

to "Fly Baby 1A" for the low-wing design, "IB" for the same

fuselage with a new set of biplane wings, and "1C" for a

strut-braced parasol monoplane wing fitted to the biplane center

section.”

The “1C” never happened…but the Fly Baby biplane (sometimes called the “Bi-Baby”) flew about six years later.

People often refer to the Fly Baby biplane as the result of adding another wing to the monoplane. Not really the case: The biplane configuration does not use the monoplane wings, replacing them with four wing panels (each about 75% of the size of the monoplane wings) and a center section. The lower wing has the stock 3-degree dihedral, but the upper one has only 1 degree. The wings are built the same way as the monoplane ones, with the exception of 1/16” plywood for the ribs instead of 1/8”.

Merely making the wings scale versions of the monoplane ones would have put the top wing directly above the cockpit, making access awkward. Instead, Pete set the center section forward, and added about 11 degrees of wing-sweep to keep the CG in the same place.

The same fuselage, tail, engine, etc are used, though the fuselage needs some additional structure to hold the cabane struts and attach the flying wires. A reinforcement bracket gets added at the firewall for the center-section wire bracing, attachment tangs are added for the flying wires, and the forward strut of the cabanes bolts to a point on the forward longerons.

The modifications do increase the empty weight of

the aircraft. In a SPORT AVIATION article, Pete says the biplane

is about 70 pounds heavier. Yet when one compares the empty

weights listed in the plans, Pete shows only a 50 pound penalty.

In any case, the biplane has 25% more wing area than the

monoplane, so the wing loading is less.

The modifications do increase the empty weight of

the aircraft. In a SPORT AVIATION article, Pete says the biplane

is about 70 pounds heavier. Yet when one compares the empty

weights listed in the plans, Pete shows only a 50 pound penalty.

In any case, the biplane has 25% more wing area than the

monoplane, so the wing loading is less.

The wing-sweep gives the Bi-Baby a bit of a chameleon look in flight. It looks like different airplanes from different angles. Many small biplanes sweep the top wing, but very few sweep the bottom wing as well (the Marquart Charger is one). The DeHavilland Tiger Moth is probably the best-known example, and from some angles this American kittycat does look like a Tiger.

It also lends itself for “Faux Fighter” paint jobs…

The Biplane instructions became an extra-cost addendum to the

standard plans in the late ‘60s, with Pete charging $15

additional. The biplane addendum was merged into the full plans

set after Pete's death.

There is one problem with the biplane addendum: They aren’t really finished. Pete was a bit of a prickly person, a perfectionist, and the word is that he had a falling-out with his draftsman about midway through the writing of the plans. So the beautiful, clean diagrams that enhance the main plans and the start of the biplane plans taper off to sketches; the typewritten text tapers to notes written on the sketches. The sketches aren’t bad, they do illustrate the points needed, but they never get to some of the details of the rigging. In the introduction, Pete apologies for the state of the plans and says an improved version was on the way…but it never happened. That’s part of the reason, after Pete’s death, that the person selling the plans started including them for free.

I’ve never flown a Fly Baby biplane myself, but I’m told that

they climb better than the monoplane (better wing loading). All

the struts and the additional frontal area on the wings do tend

to slow the airplane. An A65 gives acceptable performance for a

monoplane, but a C85 or O200 might be a better pick for the

bipe. The man who originally checked me out in the (monoplane)

Fly Baby talked about the biplane for a bit. It flew fine, but,

compared to other biplanes he’d flown like the Starduster, it

didn’t really stand out.

So, why build a Fly Baby biplane? Well, it’s one the few all-wood biplane designs out there...and unlike some, it's got a decent amount of room for the pilot.

Wood is very pleasant media to work with, and doesn’t require learning welding or setting up a workshop that sees burning slag thrown about occasionally. Second, you can reduce the time before completion of a Fly Baby by building the monoplane wings first, then building the biplane wings while you have fun with the airworthy airplane. Switchover from monoplane to biplane configuration takes two people about an hour.

Downsides of the biplane? Well, as mentioned, its slower than

its single-wing counterpart. It *does* take longer to build, due

to two additional wing panels and the center section, and the

modifications required to the fuselage. The biplane wings don’t

fold, either.

On the plus side, the biplane configuration gets

rid of one of the least-liked features of the stock Fly Baby:

The stiff, unsprung, un-bungeed, landing gear. On the monoplane

Fly Baby, the landing gear is part of the wing-bracing system,

thus the only shock-absorbing feature of the landing gear is the

few PSI in the fat tires. The ‘Baby is hell-for-stout; it’s

almost impossible to damage the gear in all but a full-blown

crash, but it does lead to some horrific bounces.

On the plus side, the biplane configuration gets

rid of one of the least-liked features of the stock Fly Baby:

The stiff, unsprung, un-bungeed, landing gear. On the monoplane

Fly Baby, the landing gear is part of the wing-bracing system,

thus the only shock-absorbing feature of the landing gear is the

few PSI in the fat tires. The ‘Baby is hell-for-stout; it’s

almost impossible to damage the gear in all but a full-blown

crash, but it does lead to some horrific bounces.

In contrast, adding the biplane wing set frees the gear from supporting the wings. Some builders have added spring-steel gear legs, or Cub-type bungees. However, keep in mind that a switch back to monoplane mode won’t work, then, unless the stock gear is returned as well.

We don’t know how many Fly Baby Biplanes have flown. The FAA registry, as one point, listed a dozen or so “Bi-Baby” or “Fly Baby 1B” aircraft, but, of course, there are dozens listed as merely “Fly Baby” and thus could go any way. The newest one is Karl Grubert, which first flew in May 2015. His plane shows how minor cosmetic changes can really make the machine look like it's from World War I.

Keep in mind that *any* Fly Baby can be modified to biplane

configuration. Nothing wrong with buying a monoplane and

building your own biplane wings for it. Last Fly Baby sale I’m

aware of, the plane went for $6,000 and, after a couple of days

work, it was flown 300 miles to its own home. Biplane wings

could probably be added for less than $2,000 more.

I’m only aware of two Fly Babies that were built with both sets of wings: Pete Bowers’ original airplane, and the late John Day’s British Fly Baby. Day’s airplane was on the cover of KITPLANES magazine, in both configurations, about 15 years ago.

But of all the designs, only one let a pilot stand by the airplane and say, “Hmmm…shall I fly it as a monoplane or a biplane today?” And that’s Pete Bowers’ “Fly Baby.”

The “1C” never happened…but the Fly Baby biplane (sometimes called the “Bi-Baby”) flew about six years later.

People often refer to the Fly Baby biplane as the result of adding another wing to the monoplane. Not really the case: The biplane configuration does not use the monoplane wings, replacing them with four wing panels (each about 75% of the size of the monoplane wings) and a center section. The lower wing has the stock 3-degree dihedral, but the upper one has only 1 degree. The wings are built the same way as the monoplane ones, with the exception of 1/16” plywood for the ribs instead of 1/8”.

Merely making the wings scale versions of the monoplane ones would have put the top wing directly above the cockpit, making access awkward. Instead, Pete set the center section forward, and added about 11 degrees of wing-sweep to keep the CG in the same place.

The same fuselage, tail, engine, etc are used, though the fuselage needs some additional structure to hold the cabane struts and attach the flying wires. A reinforcement bracket gets added at the firewall for the center-section wire bracing, attachment tangs are added for the flying wires, and the forward strut of the cabanes bolts to a point on the forward longerons.

The modifications do increase the empty weight of

the aircraft. In a SPORT AVIATION article, Pete says the biplane

is about 70 pounds heavier. Yet when one compares the empty

weights listed in the plans, Pete shows only a 50 pound penalty.

In any case, the biplane has 25% more wing area than the

monoplane, so the wing loading is less.

The modifications do increase the empty weight of

the aircraft. In a SPORT AVIATION article, Pete says the biplane

is about 70 pounds heavier. Yet when one compares the empty

weights listed in the plans, Pete shows only a 50 pound penalty.

In any case, the biplane has 25% more wing area than the

monoplane, so the wing loading is less.The wing-sweep gives the Bi-Baby a bit of a chameleon look in flight. It looks like different airplanes from different angles. Many small biplanes sweep the top wing, but very few sweep the bottom wing as well (the Marquart Charger is one). The DeHavilland Tiger Moth is probably the best-known example, and from some angles this American kittycat does look like a Tiger.

It also lends itself for “Faux Fighter” paint jobs…

There is one problem with the biplane addendum: They aren’t really finished. Pete was a bit of a prickly person, a perfectionist, and the word is that he had a falling-out with his draftsman about midway through the writing of the plans. So the beautiful, clean diagrams that enhance the main plans and the start of the biplane plans taper off to sketches; the typewritten text tapers to notes written on the sketches. The sketches aren’t bad, they do illustrate the points needed, but they never get to some of the details of the rigging. In the introduction, Pete apologies for the state of the plans and says an improved version was on the way…but it never happened. That’s part of the reason, after Pete’s death, that the person selling the plans started including them for free.

So, why build a Fly Baby biplane? Well, it’s one the few all-wood biplane designs out there...and unlike some, it's got a decent amount of room for the pilot.

Wood is very pleasant media to work with, and doesn’t require learning welding or setting up a workshop that sees burning slag thrown about occasionally. Second, you can reduce the time before completion of a Fly Baby by building the monoplane wings first, then building the biplane wings while you have fun with the airworthy airplane. Switchover from monoplane to biplane configuration takes two people about an hour.

In contrast, adding the biplane wing set frees the gear from supporting the wings. Some builders have added spring-steel gear legs, or Cub-type bungees. However, keep in mind that a switch back to monoplane mode won’t work, then, unless the stock gear is returned as well.

We don’t know how many Fly Baby Biplanes have flown. The FAA registry, as one point, listed a dozen or so “Bi-Baby” or “Fly Baby 1B” aircraft, but, of course, there are dozens listed as merely “Fly Baby” and thus could go any way. The newest one is Karl Grubert, which first flew in May 2015. His plane shows how minor cosmetic changes can really make the machine look like it's from World War I.

I’m only aware of two Fly Babies that were built with both sets of wings: Pete Bowers’ original airplane, and the late John Day’s British Fly Baby. Day’s airplane was on the cover of KITPLANES magazine, in both configurations, about 15 years ago.

Return to the Stories Page

Return to the Stories Page