Seattle author and Fly Baby designer Peter M. Bowers passed

away in April of 2003, just two weeks short of his 85th birthday.

The world may remember him as the author of 26 books and over a

thousand

aviation articles, but he and the Fly Baby were an integral part of the

Pacific Northwest homebuilding scene for more than fifty years.

Updated with more pictures and the details of the sale of N500F - 16 July 2004

Where he

differed

from his contemporaries was in his scientific approach to his

hobby.

It wasn't enough to merely snap pictures of the airplanes that visited

nearby airports. Pete noted the subtle differences between

related

types, and learned how to compose the images to best-preserve the

distinctive

features of each aircraft. He categorized his photo collection to

allow faster access to data on particular aircraft. He studied

how

to make his models fly faster and farther.

Where he

differed

from his contemporaries was in his scientific approach to his

hobby.

It wasn't enough to merely snap pictures of the airplanes that visited

nearby airports. Pete noted the subtle differences between

related

types, and learned how to compose the images to best-preserve the

distinctive

features of each aircraft. He categorized his photo collection to

allow faster access to data on particular aircraft. He studied

how

to make his models fly faster and farther.

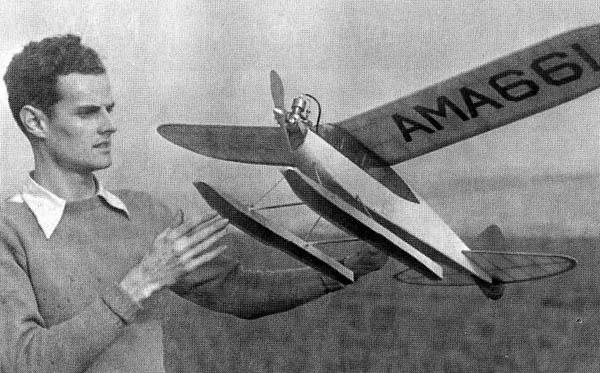

Like many who design and build model aircraft, he sent photos of his creations to the national magazines that covered the hobby. But instead of the usual blurry snapshots, the editors received clear, crisp photos and drawings, and well-written descriptions of the aircraft. Soon, Pete was writing for several national modelling magazines…while still in high school!

His photographic skills kept improving. Soon, Pete was having photos published in non-aviation magazines such as LOOK. He began submitting photos to JANES ALL THE WORLD AIRCRAFT in 1941, and continued the practice for the next fifty-one years.

Pearl

Harbor

led to Pete's joining the Engineering Cadet program for the U.S. Army

Air

Forces. Commissioned in 1943, he was eventually assigned to the

China/Burma/India

theater as a maintenance officer.

Through this time, he maintained his fascination with photography. Film for his civilian camera was non-existant overseas, but he found that photo-reconnaissance aircraft usually didn't expose their whole film magazines while on a mission. Since the magazines didn't include light shielding to aid the transfer, he learned how to transfer these leftover snippets to his camera completely by feel, in total darkness.

By the end of the war, his abilities to photograph and categorize aircraft led to his being placed in charge of the U.S. Army Aircraft Recognition Program.

During

his time

at Boeing, Pete worked a variety of tasks. Engineers who can

write

well are relatively rare, so he was often brought in as a "hired gun"

to

edit and improve company proposals.

During

his time

at Boeing, Pete worked a variety of tasks. Engineers who can

write

well are relatively rare, so he was often brought in as a "hired gun"

to

edit and improve company proposals.

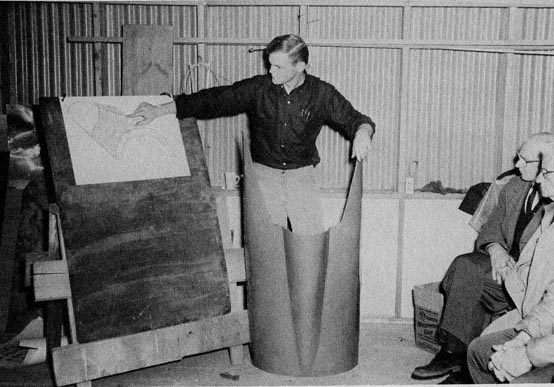

Engineers with Pete's understanding of aviation history are even rarer, so Pete was brought in when the company decided to make a full-scale, flying replica of the B&W, Boeing's first aircraft. The replica is currently in the Seattle Museum of flight. Pete also wrote historical articles for various company publications.

Pete's legendary camera skills were occasionally used, as well. In one of the more famous cases, Pete arranged a "formation" photograph of the Dash 80, Boeing's 707 jetliner prototype…and Pete's own replica of a 1911 Curtiss Pusher. Pete arranged for the Dash 80 crew to fly a low approach at Boeing Field while Pete himself "flew" formation with a pickup truck carrying the cameraman.

For his own flying, Pete's primary interest was in low-powered or even non-powered aircraft. Over the years, he owned a number of aircraft, from a Ford-powered Pietenpol to the Curtiss replica, from a Sorrell biplane to a Baby Bowlus glider.

Like many aeronautical engineers, Pete started thinking of building an aircraft of his own design. In the mid 1950s, he began designing what he called a "jazzy personal runabout," using a fuel-injected 85 HP Continental engine. The airplane would be made of wood, as Pete had no experience with any other construction material.

Paul Poberezny had begun the Experimental Aircraft Association in 1952, and individual chapters were springing up all across the country. Pete's discussions with other Seattle-area pilots revealed others with an interest in building their own aircraft.

In 1956,

a meeting

was held at Seattle's Roosevelt Hotel. A dozen or more interested

pilots attended the formation meeting for Experimental Aircraft

Association

Chapter 26. Pete was elected the first President, a position he

would

hold for the next eight years. Regular meetings for the chapter

began

at Pete's home, which became the center for homebuilding in the Seattle

area. Chapter 26 has been in operation for the last 47 years.

In 1956,

a meeting

was held at Seattle's Roosevelt Hotel. A dozen or more interested

pilots attended the formation meeting for Experimental Aircraft

Association

Chapter 26. Pete was elected the first President, a position he

would

hold for the next eight years. Regular meetings for the chapter

began

at Pete's home, which became the center for homebuilding in the Seattle

area. Chapter 26 has been in operation for the last 47 years.

In the meantime, Pete wasn't making any progress on his own design.

Tom Story in Oregon built a Wimpy. After flying it for several years, he sold it to George Bogardus. Bogardus dubbed the airplane "Little Gee Bee." In the immediate post-war period, homebuilt aircraft were banned in nearly all States but Oregon. Bogardus flew Little Gee Bee to Washington DC to prove that homebuilts could be just as safe as production aircraft. The CAA eventually approved a new "Amateur Built" licensing category.

After

selling

his Wimpy to Bogardus, Tom Story decided to build several more aircraft

that included some of his own improvements. These were the Story

Specials. Serial Number Two

was

flown for several years, then placed on sale. A charter member of

Chapter 26, Cecil Hendricks, found the airplane and convinced Pete

Bowers

and another man to put the money together and buy the aircraft.

After

selling

his Wimpy to Bogardus, Tom Story decided to build several more aircraft

that included some of his own improvements. These were the Story

Specials. Serial Number Two

was

flown for several years, then placed on sale. A charter member of

Chapter 26, Cecil Hendricks, found the airplane and convinced Pete

Bowers

and another man to put the money together and buy the aircraft.

The stage was set for the development of the Fly Baby.

The aircraft would essentially be EAA's first "standard" design; one of the conditions of the contest would be that the plans would be published in EAA's "Experimenter" magazine. The designs would be judged at the EAA's annual convention at Rockford in 1960.

Pete had his original concept for his jazzy runabout, which he had given the name of one of his successful models of the 1930s: "Fly Baby." It didn't fit the ease of construction requirement of the contest, and its higher performance level would probably make it a bit tougher to fly, too.

Pete

designed a

second airplane for the contest. Based on the well-proven

aerodynamic

layout of the Story Special, the Fly Baby II was a much simpler version

of the original Fly Baby. A partner stepped forward to build the

contest airplane while Pete built his high-performance design, but the

partner was transferred soon after beginning construction. Pete

bought

the components to finish it for the contest.

Pete continued to fly and refine the airplane. He invited other local pilots to fly it as well. Six weeks before the judging in 1962, disaster struck: A pilot flying the aircraft got caught in the mountains and crashed.

The

tail surfaces

were pretty much intact, and the wings weren't in too bad of shape, but

the fuselage was broken and twisted.

The

tail surfaces

were pretty much intact, and the wings weren't in too bad of shape, but

the fuselage was broken and twisted.

Pete got the aircraft back home. He was staring at it disconsolately in his garage, when two passersby stopped to talk. They were fellow Boeing engineers on temporary assignment to Seattle. They didn't see the task as insurmoutable, and they volunteered to pitch in.

In one sense, the accident was a blessing in disguise. The Fly

Baby had shown marginal pitch stability, and Pete had been

contemplating

adding a wider horizontal stabilizer. Pete and the two visitors

managed

to get a new fuselage built and the plane repaired in time for

trailering

to Rockford.

One additional change: The FAA has rules that state short

numbers (Like N13P) should be reserved for small aircraft that couldn't

fit longer ones. The FAA demanded an affidavit that Pete's plane

was such an example. It wasn't the case, so Pete asked for

N500F as a replacement number and they painted the new number on the

side of the new fuselage. Pete said the "F" was an

abbreviation for the type of copying system to be used for the

plans...and the "500" was how many plans he expected to sell.

Before his death in 2004, Pete saw plan sales exceed 5,000.

The Fly Baby came out the winner. Pete wrote up the building instructions, which were published in "Experimenter" magazine over a two-year period. He had anticipated selling about 500 set of plans, but actual sales exceeded 5,000.

The simple construction and basic aerodynamics of the Fly Baby lent itself to extensive experimentation. Pete used N500F, the prototype, as a test bed for modifications ranging from an externally-mounted baggage pod to a simple modification to incorporate biplane wings.

One

experiment

had mixed results. Pete installed floats from an Aeronca to try

out

on the Fly Baby. Unfortunately, the buoyancy was not

correct.

When Pete taxied N500F down the floatplane ramp at Renton field, the

Fly

Baby did a graceful forward somersault to the inverted position.

Pete swam out from the submerged cockpit, and surfaced, shouting, "Get

a camera! Get a camera!"

One

experiment

had mixed results. Pete installed floats from an Aeronca to try

out

on the Fly Baby. Unfortunately, the buoyancy was not

correct.

When Pete taxied N500F down the floatplane ramp at Renton field, the

Fly

Baby did a graceful forward somersault to the inverted position.

Pete swam out from the submerged cockpit, and surfaced, shouting, "Get

a camera! Get a camera!"

One of the best-known cases was the biplane-wing adaptation. Contrary to popular opinion, this does not use the stock wing with just an upper wing and center section added...it's four new wing panels. Each wing panel is about 75% of the size of the wing panels on a monoplane Fly Baby...hence the total wing area is higher, but not twice that of the monoplane.

The wings aren't just scaled copies of the stock wings, either...the biplane wings are actually swept back about seven degrees. If straight wings had been installed, the upper wing would have ended up directly above the cockpit, and access would have been very difficult. So Pete designed a center section to the top wing and installed it forward of the cockpit. If the upper wing had just been straight, then, the combined Center of Pressure would have shifted fairly far forward, giving the plane an aft CG. So Pete had to sweep the wings to keep the CG in the right spot. It's actually fairly attractive, visually... from certain angles, the plane looks a bit like a Bucker Jungmeister.

The Biplane version was successful...or, at least, flew all right. The Fly Baby isn't a fast airplane to start with...adding a whole second wing and the extra bracing wires don't help. If you *must* have a biplane, the Fly Baby isn't a bad choice. But it's a lot less draggy as a monoplane.

In another instance of experimentation, Pete decided to try to tow

gliders

with N500F. He installed a remote tow-cable release on the

tailwheel

spring of the Fly Baby, then went to the local FAA on a Friday with the

waiver paperwork necessary for glider tow. The FAA inspector had

just come back from vacation, and hurriedly signed off on the

glider-tow

waiver. Pete spent the weekend towing gliders aloft with the Fly Baby,

especially his own Baby Bolus.

Come Monday, the FAA inspector had whittled down the stack of papers

that had collected in his in-basket over his vacation. There, he

found a notice from FAA headquarters banning the issuance of

glider-tow

waivers to homebuilts! So N500F had just a single weekend of

towing.

The hook was retained, though, as it's very convenient for hand

propping.

Pete sold N500F to an Indiana man in the early 1990s. However, Bob Dempster of Renton purchased this historic aircraft and brought it back to the Pacific Northwest. It has subsequently been obtained by Seattle's Museum of Flight, and will soon be placed on display in the Great Gallery.

His books include nine editions of his Guide to Homebuilts, Unconventional Aircraft, Guide to Aviation Photography, Boeing Aircraft Since 1916, and Of Wings and Things, a compilation of his GAN columns.