But....this isn't really Pete's first Fly Baby homebuilt. There's a back-story here that's kind of strange. It's right out of adventure novels like "Prisoner of Zenda" or "The Man in the Iron Mask." In a way, N500F is the Pretender to the Throne. It's NOT the first Fly Baby, and I'm not referring to Pete's earlier free flight models that he called "Fly Baby."

What's more, depending how you interpret events, N500F didn't qualify for 1962 competition, and should not have won it.

Yet...it did. Whether its victory was legitimate depends on your interpretation both of the EAA rules and some FAA rulings.

How did that happen? Let's take a look.

Background: The EAA Contest

In 1957, the Experimental Aircraft Association announced its first design contest. The entrants would be judged on how easy they were to fly, how difficult and expensive they were to build. To encourage the lowest cost of ownership, the designs would have to have folding wings and be trailerable.The aircraft would essentially be EAA's first "standard"

design; one of the conditions of the contest would be that

the plans would be published in EAA's "Experimenter"

magazine. The designs would be judged at the EAA's

annual convention at Rockford in 1960.

The rules actually evolved, over the next several years. This summarizes the rules, and the changes.

Three other requirements come key, here. The contest changed from requiring working drawings to requiring drawings with sufficient detail to allow a typical builder to actually construct the thing. A three-view would not be sufficient; now, the winner would have to meet a rather relative standard as to whether the documentation provided was sufficient.

The winner of the contest was to receive $2,500 in prize money. However, originally, the designer would have to turn the rights over to EAA itself. The contestants balked at this, so the requirement was eliminated.

One requirement stayed the same: That, prior to demonstration at the contest, the plane would have to build 50 hours of flight time. If you're familiar with the FAA's rules for homebuilts, this requirement is pretty logical. The FAA requires most homebuilts undergo a 40-hour test program, so this requirement basically established the plane would have to be out of the test period.

The First Fly Baby

Pete had a concept for his jazzy runabout, which he had given the name of one of his successful models of the 1930s: "Fly Baby." It didn't fit the ease of construction requirement of the contest, and its higher performance level would probably make it a bit tougher to fly, too.

Pete designed a second airplane for the contest.

Based on the well-proven aerodynamic layout of the Story

Special, the Fly Baby II was a much simpler version of the

original Fly Baby. A partner stepped forward to

build the contest airplane while Pete built his

high-performance design, but the partner was transferred

soon after beginning construction. Pete bought the

components to finish it for the contest.

The result was the familiar configuration, low wing, open

cockpit, familiar wing and tail shape, A65 engine, and

rigid landing gear.

That was the Fly Baby's original registration number. This was Pete's third homebuilt, and so he requested "N3P". For reasons known only to the FAA, they gave him "Thirteen" when he asked for "Three."

N13P was covered in Sears Dacron Polyester taffeta. Pete was inspired by the paint scheme on the Boeing Dash-80 (the prototype of the 707 line) and decided to duplicate the yellow and red scheme.

A friend talked him into using automotive enamel, so it was painted School Bus yellow and "Cordovan Brown." They didn't get fancy...no trim stripes, just the yellow and maroon.

By the way, as far as I've been able to determine, N13P is the only Fly Baby that had a yellow nose bowl with a red cowling. That's a quick way to identify it on old pictures.

N13P's first flight, on July 27th, 1960, was inauspicious. The engine quit on takeoff. Pete had done a lot of taxi testing, and had run the tank low. The landing gear was banged up a bit, but there wasn't any major damage. The problem was complicated by the design of the tank....it didn't have much of a sump, so would have problems delivering fuel to the engine in three-point attitude. This was just a a week before the EAA contest in Rockford.

1960 Contest

Since the Fly Baby only had a few hours, Pete

towed it to the 1960 contest. The EAA was

having trouble lining up contestants, and had

reduced the required flight hours to just

25.

As it turned out, there was only one other

contestant there...and HE didn't have 25 hours,

either (Neal Loving's Pusher). The EAA

pushed back the judging, giving contestants

another two years.

The Fly-In coverage in Sport Aviation magazine

that year didn't get the plane quite right:

They called it a "Story Bowers Folding

Wing." Pete had a lot of history in the Story, but of

course, other than the general configuration, the

two designs didn't share any specific features.

Here's another bit of trivia: At the 1960 convention, they apparently applied registration numbers to the vertical stabilizers of homebuilt aircraft attending. Looking at the original EAA coverage of the convention, you can see the numbers on the tails of most of the airplanes pictured. N13P picked up "E2":

As an aside, can you imagine the attendees at today's Oshkosh allowing such additions to their airplanes????

Testing and FAA Woes

In the interim, Pete and his friends kept flying

the airplane. He let just about anybody with

a license fly it.

He came up with several issues. The plane

was a bit nose-heavy, and the pitch

stability. And, of course, the fuel tank

needed a deeper sump.

Not long after his return from Rockford in 1960,

Pete got a letter from the FAA. FAA's policy

was to assign short N-Numbers (such as N13P) to

aircraft that could not fit a a12-inch N-number of

the conventional 3+ digits and a letter

format. The FAA demanded that either Pete

provide a signed affidavit that his plane was too

small for a normal number, or get a new

N-Number.

Pete fought this, but eventually lost. He

decided to request N500F. The "500"

represented his guess as to the number of plans he

might eventually sell (the actual number was in

excess of 5,000) and the "F" for "Folio," the

duplication process he was going to use on the

plans to avoid the scaling errors that occur in

most copying methods.

Fateful 1962

Pete never did re-paint N13P with the new

N-number...because it crashed on April 1962.

Pete had lent the plane to a friend for a

cross-country, and he'd run it out of gas and

crashed it in the mountains. It was pretty

badly bashed.

What happened next is legendary... Pete was staring at it disconsolately in his garage, when two passersby stopped to talk. They were fellow Boeing engineers on temporary assignment to Seattle. They didn't see the task as insurmoutable, and they volunteered to pitch in. While they were at it, Pete instituted all the design changes he'd come up with during the ~2 years of experience flying N13P.

The Fly Baby Wins

And...they made it. The rebuild started on 5 May, and the first flight of the renewed airplane was the first of July...exactly one month before the convention started. The rebuild took less than two months. One heck of a job.Pete trailered N500F to Rockford, and the Fly Baby won the design contest. This time they painted it with standard dope (Cub Yellow and Randolph Boston Maroon), and even managed to include white and black "cheat stripes" between the colors to make it look prettier.

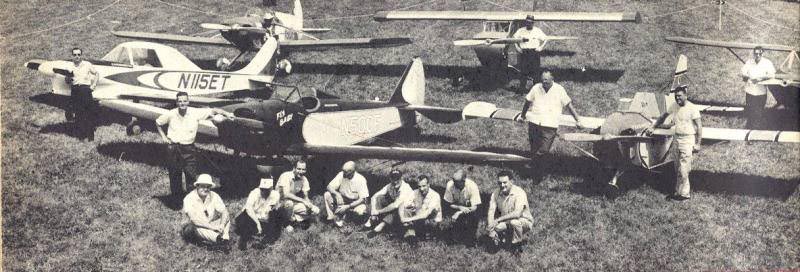

Eighteen individuals had originally entered the EAA design contest. Six aircraft were in attendance at Rockford '62. These included planes like the Turner T-40, the Nesmith Cougar, the Treft Contestor, the Lacey M-10, and the Spezio Tuholer. Neal Loving's pusher, the only competitor in 1960, hadn't made it to the 1962 convention.

Pete saw the Tuholer as his primary competion:

"First off, I figured he'd get a big advantage in being two-seat, which in view of the preference for two-seaters in the 1960 contest should overcome a lot of shortcomings in other areas. I didn't figure that he'd lost much for having a steel tube fuselage. Wood was cheaper and in my opinion easier to work with, but lots of people would far rather have that ironwork around them. He got a big cost break by using the Lycoming ground unit engine, and had lots of speed over "Fly Baby", but with his greater weight and shorter span, "Baby" should take him on easy flying, slow landing, etc. We figured it would be pretty close."

Or Did It...?

There's a fundamental question here: Is N500F the same airplane as N13P?

On the surface, that shouldn't be

important. N500F was the airplane evaluated

at Rockford 1962; it won the contest on its

merits. According to the judges, it was the

best of the contestants.

But... were the rules followed? Remember

the rule that required all entries had at least 50

hours of flight time (later reduced to 25)?

N500F didn't have 25 hours of flight time.

The only way it could be considered to qualify is

if was the same airplane as N13P.

Is it?

Well, let's look at

what was necessary:

- New Fuselage

- New wing leading edges

- New landing gear Vees

- New engine

- New engine mount

- New cowling

- New fuel tank

- New paint

- New registration number

- Main wing structure

- Tail surfaces (not the vertical stabilizer, it is built-in to the aircraft

- Main axle (according to Pete, pounded back into shape.

- ... and, in fact, any of the metal parts that

could be hammered back into shape.

The diagram below shows the portion of the airplane that were original to N13P, vs. that constructed new for the contest. Kind of highlights how much had been changed....

The FAA Weighs In

According to Pete, the FAA determined that N500F

*was* just a repaired N13P: "A big break

came from FAA, which ruled that the repair,

actually about 60 percent new airplane when you

count the engine, mount, and tank, was just that

and that the lengthened fuselage was not

considered a major alteration that had to be

proved out by a long flight test program."

So according to the FAA, it was the same

airplane.

I presume Pete had this in writing, to present to

the judges at Rockford and forestall exactly this

kind of question.

One thing in his favor, I think, is that Pete

didn't try to hide what had happened. Most

of the information I've written about is in the

very first Fly Baby article he wrote for Sport

Aviation magazine. It was published in

December 1962. I think if all the facts had

been a surprise to the other contestants, they

would have raised Cain about it.

In the article, Pete mentions that he'd had to

take a business trip during the rebuild...and

spent a couple of days with Neal Loving, one of

his competitors. Since the crunched N13P was

already in the middle of its metamorphosis to

N500F, I don't think Pete would have avoided

talking about it to Mr. Loving.

I believe Pete was completely on the up-and-up about his problems. The FAA letter would have backed him up sufficiently. However, one has to kind of wonder. Pete had an existing relationship with the Seattle FAA guys. It's certainly possible they did him a favor.

One Other Factor

Right now, it sounds to me like the contest

judges could have gone either way. There's

another factor that might have affected their

decision.

The major goal of the contest was to establish an

easy-to-build homebuilt design, with the

construction process well documented.

It's quite possible that Pete was, far and away,

the best qualified to write a series of articles

on building an airplane. That was probably a

major factor in letting the Fly Baby remain as a

competitor, and, of course, in the eventual

victory of the Fly Baby.

(I'm indebted to John Smutny and Ruth Weston for the great

pictures of N13P).

Return to the Stories Page

Return to the Stories Page