I've made several posts, over the

years, about my leather jackets. With fall coming on, it's

about time for a bit of history, and a bit of guidance, for when

you're aiming to look like a well-dressed open-cockpit aviator.

A Bit Of History

First off, where did the leather-jacket tradition come from?

It's pretty simple, really: Prior to the era of modern synthetic fabrics, leather was the only flexible, wearable material that the wind couldn't penetrate. The early pilots didn't discover "wind chill," but the speeds of even the early airplanes gave a full-up demonstration of its effects. Early aviators needed clothing that the wind couldn't push through, and leather was elected.

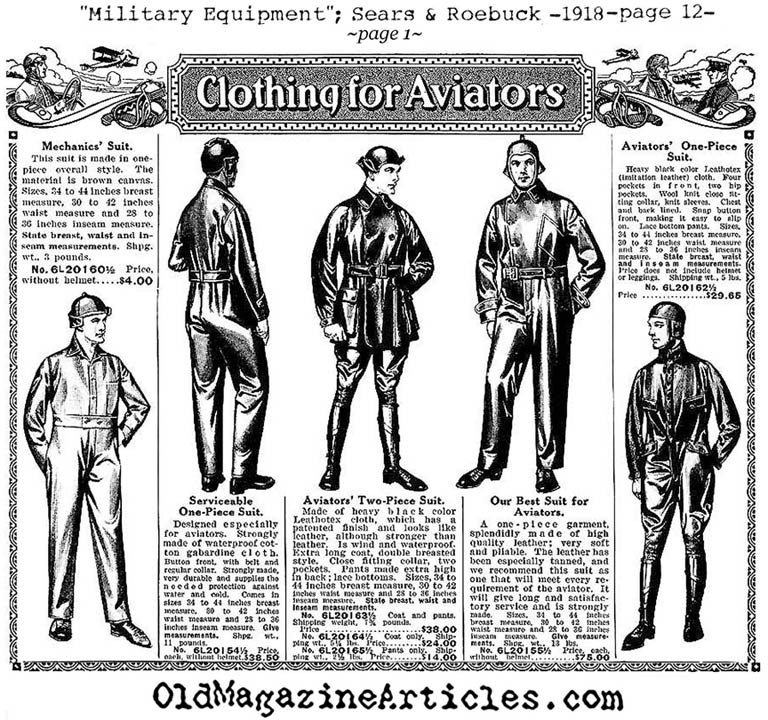

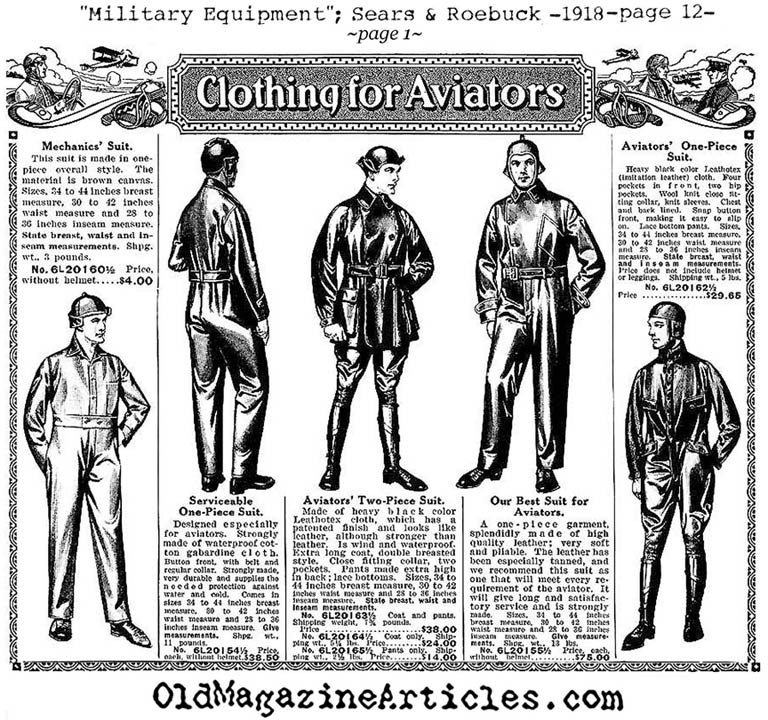

Notice there ARE leather substitutes (Waterproofed gabardine, "Leathotex"), but notice the price difference between the faux leather and the gent in the genuine leather article.

Which one is the one in real leather? The one all the guys in fake leather are looking at admiringly... the only guy who's boldly looking straight at the person reading the catalog. Advertising psychology was NOT invented in the 1950s....

The other reason leather remained popular (in

spite of the price) is how it withstood the rigors of the

cockpit environment. Cockpits back then weren't smooth

vinyl-plated cocoons. There were bolt heads, panel edges,

and sharp-edged pointy things everywhere. Waterproofed

Gabardine and the Leathotex undoubtedly looked fine out of the

box, but they probably got torn to pieces relatively

quickly.

The other reason leather remained popular (in

spite of the price) is how it withstood the rigors of the

cockpit environment. Cockpits back then weren't smooth

vinyl-plated cocoons. There were bolt heads, panel edges,

and sharp-edged pointy things everywhere. Waterproofed

Gabardine and the Leathotex undoubtedly looked fine out of the

box, but they probably got torn to pieces relatively

quickly.

Most flying togs were made from cow or horse leather, which are pretty stiff and hard when they complete the tanning process. It takes concerted effort to actually cut leather; you can scratch it, but it won't affect its weather-tightness.

Plus, of course, real leather won't burn.

The horse and cow leathers were tough, but also incredibly stiff when new. They needed to get worked in, to make them more flexible. There are stories of aviation cadets sleeping atop their brand-new leather jackets to work on softening them up. Much good THAT did. According to a modern expert, those coats could take ten years to break in.

Horse-leather became a lot cheaper as the 20th century wore on. People were selling their carriages to buy cars, and the militaries were even getting rid of their cavalry horses.

Horses and cows weren't the only leather contributors. Goatskin was popular as well; it's a bit softer (and hence doesn't have as much of a breaking-in problem) but is actually more durable. Sheep provided their input too, culminating in the Irvin and B-3 jackets of WWII. The biggest problem with these types of coats is that the goats and sheep are pretty small...it takes more of them to make a jacket, which complicates your supply process and matching the various skins.

For a real extreme, check out Roscoe Turner to the right...he's wearing a lion-skin flying coat. Note the paws have been turned into gloves. Turner used to fly with a lion cub named "Gilmore"... wonder what Gilmore thought of this coat?

(Note: Modern leather-preparation techniques have, to a large part, lost this armor-like ability. People want "soft" leather now, and these more-supple preparations seem to make the coats more vulnerable to damage. Be warned....)

By the 1930s, the world's militaries were getting away from open cockpits. They might open the canopy for takeoff and landing, but the bulky leather coveralls or long coats were no longer needed. The US Army Air Corps, the US Navy, and Britain's RAF all developed standardized flying jackets. These have come down as the "bomber jackets" still popular today, and are still the primary styles available to the open-cockpit aviator.

It's also what Douglas MacArthur preferred...most statues of him show him with an A-2, even the one at West Point. Strangely enough, one of the first steps of the new Army Air Force (created in 1941) was to get RID of the A-2! They stopped procuring them in mid-1942. However, they had such a large stock on-hand, they were able to issue them to new aviation cadets for the next two years.

A-2 replicas are probably the most common; just about any pilot shop sells them. However, few of them...even the ones claiming to be "authentic replicas" or "made to the same specification"... totally match the wartime jackets. It's a bit of a pet peeve of mind.

How do they differ?

How do they differ?

The look-alike A-2s tend to differ in one major area: The collar shape. Some have a broad suit-like collar, others have a knit collar like an athletic jacket (or the original A-1). Either works fine in a Fly Baby, but if you're trying to get something that looks close to an A-2 cheap and close, pay attention to the collar. Regular A-2s have kind of a stand-up collar with snaps. Regular A-2s have the epaulets atop the shoulders, of course. Pocket configurations can sometimes differ as well (some jackets eliminate the external pockets).

Note, from the flyability point of view, there's nothing wrong with a jacket that departs from the A-2 standard. It'll often just look like a civilian flying jacket from the same era. The "Indiana Jones"-type jacket is a case in point...the moviemakers deliberately didn't want Indy's coat to look like a "Bomber jacket", but ended up with something that looked close to an A-2.

There's only one key feature to ensure your jacket has: The knitted cuffs. Without them, the sleeves can act as scoops and pull cold air into the jackets. The knitted bottom of the jacket is nice, too, but in the seated position, there's usually not much of a gap.

The Navy's G-1 flying jacket is a bit newer than

the A-2; it came out in the mid- to late-30s. It is

roughly similar to the A-2 design, but with some major design

differences.

The Navy's G-1 flying jacket is a bit newer than

the A-2; it came out in the mid- to late-30s. It is

roughly similar to the A-2 design, but with some major design

differences.

The most obvious is the mouton collar, basically the wool of a sheep with a bit of hide attached. It gives a good bit of warmth around the neck, plus smoothness...important when your head is on a swivel looking for Zeros.

The standard jacket uses goatskin, with a distinctive pebbled appearance vs. the smooth finish of the A-2. This led to the nickname of the G-1: "Goat Coat." As mentioned above, goat is very durable and comfortable.

There are other differences, such as no epaulets, and an improved cut that restricts one's motion less.

The big difference with the G-1 is that it has been authorized wear for Naval Aviators nearly continuously since the 1930s. The Air Force got away from leather coats for a number of years, but continuous generations of sailors and Marines have earned their Goat Coats since before the Second World War (there was, apparently, a five-year gap in the late '70s).

Where Army and Air Force pilots generally were allowed only one unit patch on their flying jackets, the tradition in the Navy is to retain patches from previous units or deployments. It's kind of like the modern equivalent to sailor's tattoos... you can tell where a pilot has been and what he's done by the patches on his G-1.

The A-2's main celebrity is MacArthur, but most famous wearer of the Navy G-1 is Tom Cruise, in "Top Gun." The movie caused a real surge of interest in the G-1 jacket. A lot of interest is for jackets that are already covered with patches, so you see things like 19-year-olds wearing patches claiming to be an F-14 pilot. The legitimate jackets are far outnumbered by the duplicates.

Modern G-1s, like the A-2 replicas, have insulation that wasn't in the WWII versions. The mouton collar makes the G-1 a pretty good choice for open-cockpit wear. G-1s that are accurate in design can flip up the collar and button it across, protecting one's neck from the icy blast.

I'm going to lump these together due to their similar style.

Les Irvin got his original fame as the designer of one the most practical parachutes, but his company branched out into pilot wear in the 1930s. He designed the classic Irvin jacket worn by the RAF during WWII and after.

The Irvin is a shearling jacket; basically the outside of a sheep turned inside out. The wool is on the inside, the leather on the outside. The entire intention of the coat is warmth. The collar shows the wool, and there are straps to wrap it up around the face.

One problem with the Irvin: It was hard to

wear with a Mae West (inflatable life jacket). Either it

went over the collar and sat very high, or the wearer had to

feed the collar through the smallish opening in the life

jacket. Neither was really workable in a "scramble"

situation. Often, pilots would cut the entire collar off.

One problem with the Irvin: It was hard to

wear with a Mae West (inflatable life jacket). Either it

went over the collar and sat very high, or the wearer had to

feed the collar through the smallish opening in the life

jacket. Neither was really workable in a "scramble"

situation. Often, pilots would cut the entire collar off.

The celebrity Irvin jacket wearer? Monty himself...Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, to you folks.

The AAF B-3 was introduced a bit later. The design is almost identical... a shearling jacket with a broad collar and straps.The main differences is that the Irvin jacket has a belt around the waist, where the B-3 would have straps on either side. The Irvin also had zippers on the sleeves to accommodate heavy gloves. Neither coat would normally have pockets, but they were often added by crewmen and most reproductions include them.

You tended to see the B-3 on bomber crewmen, especially in airplanes with open gun positions. The most famous wearer? General George Patton.

I may not be quite as famous as Patton, but I own a B-3 in addition to my A-2. Believe me, if you're afraid of being cold while flying your Fly Baby in chilly weather, get a B-3.

A Bit Of History

First off, where did the leather-jacket tradition come from?It's pretty simple, really: Prior to the era of modern synthetic fabrics, leather was the only flexible, wearable material that the wind couldn't penetrate. The early pilots didn't discover "wind chill," but the speeds of even the early airplanes gave a full-up demonstration of its effects. Early aviators needed clothing that the wind couldn't push through, and leather was elected.

The early aviators were generally rich men;

they owned automobiles which were practically as open as the

aeroplanes of the day, and hence probably already owned

leather coats like our natty Curtiss pilot above. When

World War I came around, most of the pilots in the service

weren't rich men...and, even back then, leather was more

expensive. Here's an ad (courtesy of OldMagazineArticles.com)

that shows a 1918 Sears and Roebuck catalog page for Aviator

wear.

Notice there ARE leather substitutes (Waterproofed gabardine, "Leathotex"), but notice the price difference between the faux leather and the gent in the genuine leather article.

Which one is the one in real leather? The one all the guys in fake leather are looking at admiringly... the only guy who's boldly looking straight at the person reading the catalog. Advertising psychology was NOT invented in the 1950s....

The other reason leather remained popular (in

spite of the price) is how it withstood the rigors of the

cockpit environment. Cockpits back then weren't smooth

vinyl-plated cocoons. There were bolt heads, panel edges,

and sharp-edged pointy things everywhere. Waterproofed

Gabardine and the Leathotex undoubtedly looked fine out of the

box, but they probably got torn to pieces relatively

quickly.

The other reason leather remained popular (in

spite of the price) is how it withstood the rigors of the

cockpit environment. Cockpits back then weren't smooth

vinyl-plated cocoons. There were bolt heads, panel edges,

and sharp-edged pointy things everywhere. Waterproofed

Gabardine and the Leathotex undoubtedly looked fine out of the

box, but they probably got torn to pieces relatively

quickly. Most flying togs were made from cow or horse leather, which are pretty stiff and hard when they complete the tanning process. It takes concerted effort to actually cut leather; you can scratch it, but it won't affect its weather-tightness.

Plus, of course, real leather won't burn.

The horse and cow leathers were tough, but also incredibly stiff when new. They needed to get worked in, to make them more flexible. There are stories of aviation cadets sleeping atop their brand-new leather jackets to work on softening them up. Much good THAT did. According to a modern expert, those coats could take ten years to break in.

Horse-leather became a lot cheaper as the 20th century wore on. People were selling their carriages to buy cars, and the militaries were even getting rid of their cavalry horses.

Horses and cows weren't the only leather contributors. Goatskin was popular as well; it's a bit softer (and hence doesn't have as much of a breaking-in problem) but is actually more durable. Sheep provided their input too, culminating in the Irvin and B-3 jackets of WWII. The biggest problem with these types of coats is that the goats and sheep are pretty small...it takes more of them to make a jacket, which complicates your supply process and matching the various skins.

For a real extreme, check out Roscoe Turner to the right...he's wearing a lion-skin flying coat. Note the paws have been turned into gloves. Turner used to fly with a lion cub named "Gilmore"... wonder what Gilmore thought of this coat?

(Note: Modern leather-preparation techniques have, to a large part, lost this armor-like ability. People want "soft" leather now, and these more-supple preparations seem to make the coats more vulnerable to damage. Be warned....)

By the 1930s, the world's militaries were getting away from open cockpits. They might open the canopy for takeoff and landing, but the bulky leather coveralls or long coats were no longer needed. The US Army Air Corps, the US Navy, and Britain's RAF all developed standardized flying jackets. These have come down as the "bomber jackets" still popular today, and are still the primary styles available to the open-cockpit aviator.

US Army Air Corps: The A-2 Flying Jacket

The specification for the A-2 was issued in the 1930s, calling for horse-hide leather, a spun silk lining, knitted wool at the cuffs, and a zipper for closure. It also had knitted wool around the bottom, sealing the jacket from drafts from below It was similar to the earlier A-1 jacket, with the major changes being the replacement of the buttons with a zipper, and replacement of a knit crew-collar with a conventional one. It's the jacket you'll see in almost all photos of WWII US Army aviators.

It's also what Douglas MacArthur preferred...most statues of him show him with an A-2, even the one at West Point. Strangely enough, one of the first steps of the new Army Air Force (created in 1941) was to get RID of the A-2! They stopped procuring them in mid-1942. However, they had such a large stock on-hand, they were able to issue them to new aviation cadets for the next two years.

A-2 replicas are probably the most common; just about any pilot shop sells them. However, few of them...even the ones claiming to be "authentic replicas" or "made to the same specification"... totally match the wartime jackets. It's a bit of a pet peeve of mind.

How do they differ?

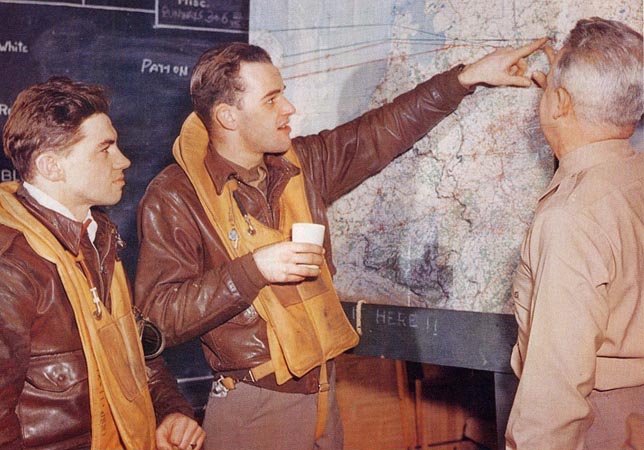

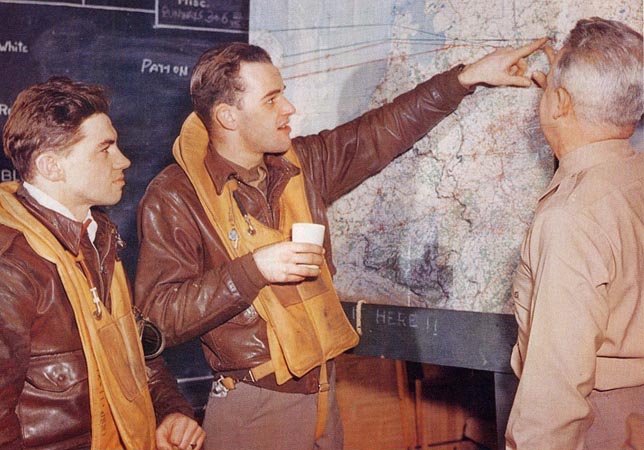

How do they differ?Color: Take a look at the color picture above and the one on the right, and compare the jacket hues to most of the replicas available today. Most of the replicas are a very dark brown, approaching black, but the wartime ones are more of a russet color. There was a bit of color variation, even then...the specification called for "seal brown," and there was some difference of opinion as to what that color actually should be. But look at the A-2s in the museums, they're all the reddish tone of the picture above. Some of that could be oxidation, but still....I've flown for the past ~20 years with a couple of A-2s, and they've served me nicely. Replica A-2s and A-2 look-alikes are commonly available. You can actually find some pretty accurate coats fairly cheaply...my last one was just over a hundred bucks, and it's lasted me nicely for over ten years. Just about any leather store carries "bomber jackets". Depending on what authenticity you want, you can often find something fairly close at one of these places.

Lining: Remember what the specification above said, relative to the jacket's interior? A "spun silk lining". They did NOT have the layer of insulation all modern jackets include! The A-2 was what we'd call a "windbreaker," only. It was not expected to warm the wearer...that was what the multiple layers of wool uniform worn UNDER the jacket was expected to do.

The difference is, the wartime A-2s weren't bulky. Notice how the jackets fit their wearers smoothly. Modern coats bulge where they shouldn't; like the Michelin Man decided to take up aviation.

I don't think there's an A-2 sold today that isn't insulated. Understandable, I guess... people expect warmth from a leather coat.

Pocket Flap Shapes: OK, a minor issue. But the lower edges of flaps on the pockets in front were NOT straight. They were a series of gentle, attractive curves. You can see it best on the gentleman on the far right of the first picture in this section. Most modern jackets don't duplicate this...straight lines, all the way.

Side-Entry Pockets: All right, the one "modern" innovation I'm in favor of. For those who don't know, you do NOT stand with your hands in your pockets when wearing a uniform. The front pockets on an A-2 are accessible only from the top, which makes it impossible for the wearer to comfortably tuck his hands inside.

Modern A-2s add a side-entry pockets UNDER the front pockets, so us civilians can ram our mitts inside to keep them warm. This isn't as much of a historical faux pas as the other items...many A-2 owners had such pockets added to their jackets.

Cut: Men wore their pants higher and thus the coats coats back then were tailored shorter. Modern A-2s are cut a bit longer than the historic ones. Seems reasonable.

The look-alike A-2s tend to differ in one major area: The collar shape. Some have a broad suit-like collar, others have a knit collar like an athletic jacket (or the original A-1). Either works fine in a Fly Baby, but if you're trying to get something that looks close to an A-2 cheap and close, pay attention to the collar. Regular A-2s have kind of a stand-up collar with snaps. Regular A-2s have the epaulets atop the shoulders, of course. Pocket configurations can sometimes differ as well (some jackets eliminate the external pockets).

Note, from the flyability point of view, there's nothing wrong with a jacket that departs from the A-2 standard. It'll often just look like a civilian flying jacket from the same era. The "Indiana Jones"-type jacket is a case in point...the moviemakers deliberately didn't want Indy's coat to look like a "Bomber jacket", but ended up with something that looked close to an A-2.

There's only one key feature to ensure your jacket has: The knitted cuffs. Without them, the sleeves can act as scoops and pull cold air into the jackets. The knitted bottom of the jacket is nice, too, but in the seated position, there's usually not much of a gap.

US Navy: G-1 Flying Jacket

The Navy's G-1 flying jacket is a bit newer than

the A-2; it came out in the mid- to late-30s. It is

roughly similar to the A-2 design, but with some major design

differences.

The Navy's G-1 flying jacket is a bit newer than

the A-2; it came out in the mid- to late-30s. It is

roughly similar to the A-2 design, but with some major design

differences.The most obvious is the mouton collar, basically the wool of a sheep with a bit of hide attached. It gives a good bit of warmth around the neck, plus smoothness...important when your head is on a swivel looking for Zeros.

The standard jacket uses goatskin, with a distinctive pebbled appearance vs. the smooth finish of the A-2. This led to the nickname of the G-1: "Goat Coat." As mentioned above, goat is very durable and comfortable.

There are other differences, such as no epaulets, and an improved cut that restricts one's motion less.

The big difference with the G-1 is that it has been authorized wear for Naval Aviators nearly continuously since the 1930s. The Air Force got away from leather coats for a number of years, but continuous generations of sailors and Marines have earned their Goat Coats since before the Second World War (there was, apparently, a five-year gap in the late '70s).

Where Army and Air Force pilots generally were allowed only one unit patch on their flying jackets, the tradition in the Navy is to retain patches from previous units or deployments. It's kind of like the modern equivalent to sailor's tattoos... you can tell where a pilot has been and what he's done by the patches on his G-1.

The A-2's main celebrity is MacArthur, but most famous wearer of the Navy G-1 is Tom Cruise, in "Top Gun." The movie caused a real surge of interest in the G-1 jacket. A lot of interest is for jackets that are already covered with patches, so you see things like 19-year-olds wearing patches claiming to be an F-14 pilot. The legitimate jackets are far outnumbered by the duplicates.

Modern G-1s, like the A-2 replicas, have insulation that wasn't in the WWII versions. The mouton collar makes the G-1 a pretty good choice for open-cockpit wear. G-1s that are accurate in design can flip up the collar and button it across, protecting one's neck from the icy blast.

Royal Air Force Irvin Jacket/Army

Air Force B-3 Jacket

Royal Air Force Irvin Jacket/Army

Air Force B-3 Jacket

I'm going to lump these together due to their similar style.Les Irvin got his original fame as the designer of one the most practical parachutes, but his company branched out into pilot wear in the 1930s. He designed the classic Irvin jacket worn by the RAF during WWII and after.

The Irvin is a shearling jacket; basically the outside of a sheep turned inside out. The wool is on the inside, the leather on the outside. The entire intention of the coat is warmth. The collar shows the wool, and there are straps to wrap it up around the face.

One problem with the Irvin: It was hard to

wear with a Mae West (inflatable life jacket). Either it

went over the collar and sat very high, or the wearer had to

feed the collar through the smallish opening in the life

jacket. Neither was really workable in a "scramble"

situation. Often, pilots would cut the entire collar off.

One problem with the Irvin: It was hard to

wear with a Mae West (inflatable life jacket). Either it

went over the collar and sat very high, or the wearer had to

feed the collar through the smallish opening in the life

jacket. Neither was really workable in a "scramble"

situation. Often, pilots would cut the entire collar off.The celebrity Irvin jacket wearer? Monty himself...Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, to you folks.

The AAF B-3 was introduced a bit later. The design is almost identical... a shearling jacket with a broad collar and straps.The main differences is that the Irvin jacket has a belt around the waist, where the B-3 would have straps on either side. The Irvin also had zippers on the sleeves to accommodate heavy gloves. Neither coat would normally have pockets, but they were often added by crewmen and most reproductions include them.

You tended to see the B-3 on bomber crewmen, especially in airplanes with open gun positions. The most famous wearer? General George Patton.

I may not be quite as famous as Patton, but I own a B-3 in addition to my A-2. Believe me, if you're afraid of being cold while flying your Fly Baby in chilly weather, get a B-3.