Surviving Without an Electrical System

June 2008

With contributions from Drew Fidoe

You don't really miss it until it's gone.

The Seattle area had a real bad windstorm in a rough December a year

and a half back. Despite living in the heart of the urban area,

our power went out and stayed gone.

It was kinda fun, an adventure, on the first night. I cooked

up a huge batch of thawing meat on the gas grill, we pulled a

cozy couch up close to the gas fireplace, watched TV on a teeny-tiny

"Watchman", and piled extra comforters on the bed.

But it got old...DARN old...after the second night. The house

had cooled to the low '50s, and it was getting boring sitting around

all evening trying to read paperback books by flashlight wrapped up in

layers of sweatshirts and blankets. By the time power came back

(about five days after the storm), we'd come to a new appreciation of

how fundamental electricity was to our lives.

The same reaction can hit Fly Baby builders, too, when they

contemplate installing an engine without a generator on their

airplane. The shock (so to speak...) hits them as they

contemplate what they'll have to do without. A starter, lights,

transponder, maybe even a comm radio.

Why do it, then?

There are a couple of good reasons. First, the lowest-cost

Continental engines are A65s, most of which don't have provisions for

starters and generators. If you're looking for the cheapest

way to get in the air, the no-generator A65 is the answer.

Second, the "overhead" involved with electrical systems on

aircraft is tremendous. You'll need a generator. A

battery. Wires. Fuses and fuse holders.

Switches. Connectors, jacks, plugs, insulated wire holders,

meters, etc., etc. etc. Not only does it have to be installed and

checked out, it's something that can go wrong over the years and have

you tearing your hair out trying to fix. When I look back to the

problems my Fly Baby has presented me in twelve

years of ownership, 90% of it has been related to the electrical system

or avionics. Plus, there's weight...a stock starter and generator

plus a conventional battery probably weighs 40-50 pounds. That's

5% of your gross weight!

Throw out the darn stuff, I say. Install just what you're going to

need, to support the kind of flying you plan to do.

Earlier this year, one builder was getting close to completion, and

emailed me for some advice as to how much of an electrical system he

needed. I cc'd Stringbag's owner, Drew Fidoe, and together we

came up with some advice.

Let's look at some aspects of the no-electrical-system world.

No Starter

If you won't have a starter, do one thing for me, first off:

Pile up a stack of bibles, Torahs, Korans, cases of Scotch Whiskey,

bunny rabbits, or WHATever you consider holy, and please swear: "I will never hand-prop my

airplane unless it's tied to something so it can't get away."

People are afraid of being hit by the prop, but in ~25 years, I've only

met one guy who has been injured by the prop when hand-propping.

But I've met a half-dozen or more that had their planes run away from

them.

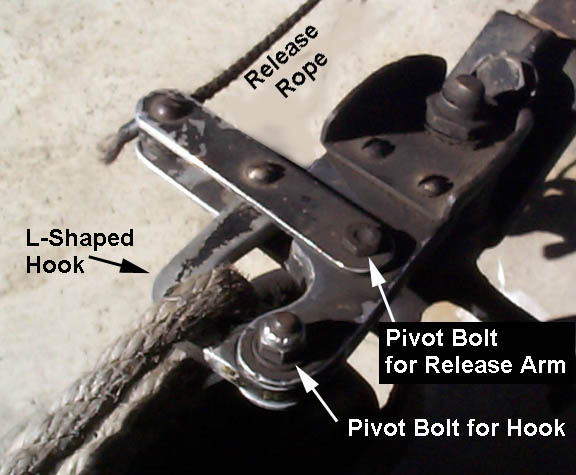

The best solution

for securing the airplane is a remote-release hook, like I describe in

a separate article. If you don't

want to build one you can buy a glider hook from Wag-Aero; they're

probably nearly $400 by now, but it gives you the advantage of a known

quantity.

The best solution

for securing the airplane is a remote-release hook, like I describe in

a separate article. If you don't

want to build one you can buy a glider hook from Wag-Aero; they're

probably nearly $400 by now, but it gives you the advantage of a known

quantity.

Carry a hank of rope and a good knife in the plane at all times.

Normally, if you stop somewhere, you can just grab a loose tiedown rope

to loop through the hook. Otherwise, you can cut off a bit of

your rope to tie to a fencepost or something and leave it behind as you

taxi away.

I flew N500F for seven years, in that time I only propped the plane

once without having either someone in it or the tailhook secured.

Once was when the engine went to sleep on final when I was landing on a

15-degree day. I coasted off onto the turnoff, then got out and

flipped it to get it going again. The second time was when I was

in the middle of a big private field with no one around and

nothing available to tie do.

My normal practice at home was to tie the tail to the hook and put

chocks on both wheels. I'd start the engine, amble around and

pull the chocks, then climb in, bolt myself onto the airplane, and

reach down and pull the release handle.

Away from home, I just used the tail hook, but made sure the plane was

POINTED somewhere safe, and made double-sure the throttle was at idle

when I flipped the prop. Especially after I didn't, and the engine

started up at full throttle (the tailhook saved me).

Careful of folks who step up and offer to prop you; they PROBABLY have

experience, but maybe not.

Remember, though, that if they're pilots, you can put them in the

cockpit to hold the brakes while YOU prop. Tie down the plane

normally, use the tailhook, do all the switch-flipping, etc. yourself,

but have the guy in the cockpit to "guard the switches". Show him

the mags so he can cut them off if necessary.

When I've been at real weird out-of-the-way places, I've stationed

non-pilots to stand by the cockpit with their sweaty hand on the mag

switches and instructions on how to turn it off if things go bad.

Again, YOU'RE doing all the control and switch manipulation; they're

just there for a backup.

Finally, on hand-propping, make sure you get a bit of

instruction. The big things are to watch your footing (you don't

want to slip) and don't be TOO scared of the prop (if you're scared,

you'll stand too far away and be leaning TOWARDS the prop).

Drew adds:

If

the engine is going to be

hand-propped, does it have at least one magneto with an impulse

coupler? If not, I recommend setting one mag around 5 - 10

degrees aft

of top dead centre, and practice starting the engine on that retarded

mag. Starting the engine on a retarded magneto will greatly

minimize

propeller kick back and facilitate "first starts" after overhaul or

reactivation. Once some safe practice is complete, and any engine

glitches attended to, set the mag for standard advance prior to

flight. I learned this one the hard way...

Comm Radio

Lots of Fly Baby

drivers, including myself, use handheld radios. They work

fine. Rechargeable batteries tend to self-discharge on their own,

though, so I kind of like the idea of using normal Alkalines.

Carry a spare set of batteries in the cockpit so you can get to them

in-flight if you absolutely have to (See also the "Battery

Only"discussion below).

Lots of Fly Baby

drivers, including myself, use handheld radios. They work

fine. Rechargeable batteries tend to self-discharge on their own,

though, so I kind of like the idea of using normal Alkalines.

Carry a spare set of batteries in the cockpit so you can get to them

in-flight if you absolutely have to (See also the "Battery

Only"discussion below).

Handheld radios put out a decent amount of transmit power, but their

main limiting factor is usually that darned "rubber-duckie"

antenna. Most handheld antennas attach with a standard BNC

connector, so you can install a "real" antenna on the airplane and hook

it up to the radio. With my setup, I hear planes in patterns ~60

miles away, and people say they can hear me just fine.

You can buy a commercial aircraft comm antenna for $50 or so, or you

can try out my homebuilt antenna.

The ultimate solution for hand-held radios, of course, is what I did

with my ICOM: Installed it in the panel, power it from the

aircraft power bus, and run a remote antenna. See the separate article. You operate it just

like a regular aircraft radio.

Transponder

First off, you have to determine whether the areas you want to fly in

require a transponder.

In the US, you need a transponder to operate within Class A, B, or C

airspace. You do not

need one to operate from the typical controlled field, which are

located in Class D airspace (but, of course, if the field itself is in

Class B or C, you'll need one...).

In addition, a transponder is required if you're going to operate

within the 30 nm "Veil" around the airport at the center of a Class B

airspace. However, there's an important provision of the rule to

be aware of. The applicable reg is 14CFR 91.215 (b)(3):.

Here it is in context:

(b) All airspace. Unless otherwise authorized or

directed by ATC, no person may operate an aircraft in the airspace

described in paragraphs (b)(1) through (b)(5) of this section, unless

that aircraft is equipped with an operable coded radar beacon

transponder...

(b)(2)

All aircraft. In all airspace within30 nautical miles of an airport

listed in appendix D, section 1 of this part from the surface upward to

10,000 feet MSL;

(b)(3)

Notwithstanding paragraph (b)(2) of this section, any aircraft which

was not originally certificated with an engine-driven electrical system

or which has not subsequently been certified with such a system

installed, balloon or glider may conduct operations in the airspace

within 30 nautical miles of an airport listed in appendix D, section 1

of this part provided such operations are conducted—

(i)

Outside any Class A, Class B, or Class C airspace area; and

(ii)

Below the altitude of the ceiling of a Class B or Class C airspace area

designated for an airport or 10,000 feet MSL, whichever is lower;

So: In the US, you can operate within the 30 nm Class B Veil if

your airplane does not have an "engine-driven electrical system."

What constitutes such a system? The FAA has said the airplane

must include all three of these items:

- A generator or alternator turned by the engine of the aircraft.

and

- A regulator to condition the power generated by the alternator or

generator, and

- A battery

Get rid of any of these three items, and you don't have to have a

transponder for flying inside the Class B Veil (you DO still need a

transponder to actually enter the Class B or C airspace, though).

The obvious thing

to get rid of , here, is the generator and regulator and just operate

on the battery alone...What engineers call a "Total Loss System."

Install just a battery and charge it up in your hangar or at home

between flights. My generator wasn't working right for over a

year, and I managed just by slapping a charger on it when I put it in

the hangar. I have a starter, and had no problems with the five

or six starts I did during a typical jaunt.

The obvious thing

to get rid of , here, is the generator and regulator and just operate

on the battery alone...What engineers call a "Total Loss System."

Install just a battery and charge it up in your hangar or at home

between flights. My generator wasn't working right for over a

year, and I managed just by slapping a charger on it when I put it in

the hangar. I have a starter, and had no problems with the five

or six starts I did during a typical jaunt.

But....usually, some folks' eyes start lighting up, here. "What

about a wind generator!!!?"

It's absolutely true that a wind-driven generator does NOT qualify as

an "Engine-driven electrical system." If you have one, you don't

need a transponder to operate within the Class B Veil.

While there have been certified aircraft that have used wind

generators, they're pretty rare. They produce a lot of drag, and

they really don't generate that much power. See Harry Fenton's take on them.

Note that the above "loophole" for aircraft without engine-driven

electrical systems only applies to flying in the US. Drew Fidoe

has this comment for his fellow Canadians:

If

you are in Canada and flying in Class C airspace there is no waiver or

grandfathering unless you are a glider. No transponder no

airspace.

I am flying out of one of the busiest

airports in Canada, in an aircraft with no engine driven

electrics. Really, once I got my less than perfect wiring tweaked

and remember to charge the battery (and turn off all switches after

flying...check list check list :) flying battery only is a

non-issue.

Flying Battery-Only

If

you don't have a starter, you really don't need that big of a

battery.

Drew has a motorcycle battery stuck in his floorboards. It's easy

enough to put a trickle charger on them (if you've got a closed hangar)

or to just pull it out and take it home. If you do the latter,

buy two

and just keep one a'charging at home. Here's an article on Batteries and Fly Babies.

Drew adds:

I use

the 12 amp-hour GEL cell in the photo. Using a modern, Garmin

transponder and an A-5 ICOM hand-held radio I seem to be good for about

4 to 5 hours of continual transponder and radio work. The

Transponder

and radio both have low-voltage cut-outs, which is good for saving the

GEL cell battery as they do not tolerate getting fully

discharged. I

carry the standard ICOM radio battery as a back-up. The ICOM is

more

sensitive to low voltage than the Transponder, and will normally shut

off when transmitting indicating low power. Then I have to either

change batteries or shut the Tx off. Since there is no engine

driven

electrical the "low power" indication always comes on the radio when I

am transmitting, this isn't an issue, only when the low power

indication stays on is when I'm going to have trouble. This only

happened a couple of time before I realized the "problem".

I use

the 12 amp-hour GEL cell in the photo. Using a modern, Garmin

transponder and an A-5 ICOM hand-held radio I seem to be good for about

4 to 5 hours of continual transponder and radio work. The

Transponder

and radio both have low-voltage cut-outs, which is good for saving the

GEL cell battery as they do not tolerate getting fully

discharged. I

carry the standard ICOM radio battery as a back-up. The ICOM is

more

sensitive to low voltage than the Transponder, and will normally shut

off when transmitting indicating low power. Then I have to either

change batteries or shut the Tx off. Since there is no engine

driven

electrical the "low power" indication always comes on the radio when I

am transmitting, this isn't an issue, only when the low power

indication stays on is when I'm going to have trouble. This only

happened a couple of time before I realized the "problem".

I

normally simply keep the battery on a "battery maintainer" or "smart

charger" after every second or third flight. I use a battery

saver on

the radio like Ron does, I used the fitted cigarette adapter but it was

very unreliable and instead hardwired the battery saver directly to my

electrical.

If you travel somewhere and intend to RON, don't forget to bring a

charger for your radio and/or the battery in your airplane. Drew

adds: For travelling away

overnight (if I

ever do this) I have a solar cell panel which I plan to leave in the

sunlight, use transponder only when absolutely necessary, and if near

and plugs will bring my charger with me.

Don't forget to install a fuse on the power line to the radio.

Don't use the plastic in-line fuse holders; these get brittle with age

and break. Auto parts stores sell holders for single-blade type

fuses; I've got some of those and think they work well.

Drew's final comment:

Please

use fuses and breakers, one friend nearly burned is Fly Baby and a new

Microair Transponder in the process, when a wire was mistakenly shorted

out! I have breakers and fuses for the transponder, radio and

other electrics.

Comments? Contact Ron Wanttaja

.

The obvious thing

to get rid of , here, is the generator and regulator and just operate

on the battery alone...What engineers call a "Total Loss System."

Install just a battery and charge it up in your hangar or at home

between flights. My generator wasn't working right for over a

year, and I managed just by slapping a charger on it when I put it in

the hangar. I have a starter, and had no problems with the five

or six starts I did during a typical jaunt.

The obvious thing

to get rid of , here, is the generator and regulator and just operate

on the battery alone...What engineers call a "Total Loss System."

Install just a battery and charge it up in your hangar or at home

between flights. My generator wasn't working right for over a

year, and I managed just by slapping a charger on it when I put it in

the hangar. I have a starter, and had no problems with the five

or six starts I did during a typical jaunt.